The Japanese government on Wednesday took countermeasures against Okinawa over its recent move to block landfill work for a key U.S. military base transfer within the small southern island prefecture.

The central government requested the land ministry to review and invalidate the Okinawa government’s decision that has suspended work for the controversial relocation of U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma.

“We still hope to realize an early (base) relocation to the Henoko area and the return of (land occupied by) Futenma Air Station,” Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga told a press conference.

Okinawa Gov. Denny Tamaki told reporters in Naha the central government move “tramples on the will of voters shown in the (Okinawa) gubernatorial election and is totally unacceptable.”

Tamaki, who is opposed to the base transfer plan, won the Sept. 30 race, beating a major rival backed by the ruling Liberal Democratic Party led by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

The central government has been seeking to relocate the U.S. base from a crowded residential area of Ginowan to the less populated coastal Henoko area of Nago, based on the Japan-U.S. agreement in 1996.

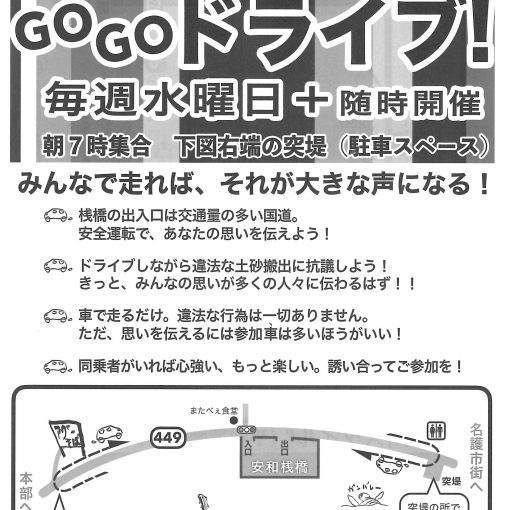

(Henoko coastal area)

“I told Prime Minister Abe that the burdens of national security should be shared by all prefectures of Japan, and asked him to establish a dialogue (between the central and Okinawa governments),” Tamaki said, referring to his meeting with Abe in Tokyo last Friday, their first since Tamaki took office.

Okinawa, which was under U.S. control between 1945 and 1972 following Japan’s defeat in World War II, hosts the bulk of U.S. military facilities in Japan and many local residents want the Futenma base moved outside the prefecture.

“We’ll do our best to realize as soon as possible the complete return of (the land hosting) the Futenma base, which is said to be the most dangerous airbase in the world,” Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya told reporters after filing the request.

The minister said he takes the will of Okinawa voters indicated in the election seriously, but at the same time said he wants to “move forward with (the relocation plan) to achieve the grand purposes” of maintaining deterrence while reducing the base-hosting burden on the island prefecture.

The government filed the request under the Administrative Complaint Review Act.

But Tamaki said, “The request is distorting the spirit of the law,” underscoring that the law is designed to protect citizens, not the government.

Iwaya denied such a view, saying the law is applicable when administrative actions are taken against not only citizens but also governing bodies.

Many Okinawa people criticized the central government’s move.

“People in the prefecture will resist as much as possible. If believing it can override our opposition, the state will be sorry for that,” said Kazunobu Akamine, a 64-year-old cook from Ginowan who takes part in protest activities in Henoko.

Hiroshi Ashitomi, 72, who heads a civic group, said, “We’ll call for international attention (to the problem) in cooperation with the prefecture.”

The landfill work was approved in 2013 by then Okinawa Gov. Hirokazu Nakaima, but his successor Takeshi Onaga revoked the approval in 2015, citing legal defects in Nakaima’s decision. In an ensuing court battle, the revocation was found illegal and Onaga rescinded it in 2016.

On Aug. 31, Okinawa again retracted the landfill work approval as instructed by Onaga before his death earlier in the month. The prefecture cited illegality in the relocation work procedure and put the base construction on hold.